Now that the span of history has shortened to the last seven hours, I can say that I lived in prehistoric times. In public buildings, schools, concert halls, churches and the like, you would see a metal box, painted red, mounted on the wall. The front of the box would feature a conspicuous glass panel. There would be printing on the glass, or maybe a placard reading “IN CASE OF FIRE BREAK GLASS”. Typically a small steel mallet was hung by the box, secured with a chain, as a means to break the glass.

The contents of the box were items deemed useful for fighting a fire. A fire hose, a fire extinguisher, an intercom for communication, even a fire axe might be obtained by breaking the glass. I saw these boxes from time to time when I was a kid.

When they built buildings later, they didn’t include these boxes. Sprinkler systems, visual and audible alarms were much more effective at controlling fires and reducing casualties than a hose or an axe in the hands of an untrained individual. The idea came into vogue that a fire alarm should be a simple lever that activated sprinklers, alarms and emergency response. But fire alarm design continued to include breaking glass. The levers were pinned in place by glass tubes or glass plates, which would break if the lever was pulled.

Breaking glass is usually considered a bad thing, almost a taboo. Suppose you offered a person a piece of glass and asked him to break it. He would be reluctant to do so. The idea was to make it so that anyone contemplating activating the fire alarm would have to overcome that reluctance. Trivial or frivolous motivations might not be sufficient. Having to break the glass should reduce the number of false alarms. As it turns out, people are so reluctant to break glass that they sometimes fail to do so, even when there is a real fire. Today’s fire alarms don’t feature breaking glass.

As everyone knows, the Centers for Disease Control, working alongside the Food and Drug Administration, spectacularly botched America’s response to the China Bug of ’19. Now we see a similar situation with the United States Department of Agriculture stepping in to make sure large lots of meat and dairy are destroyed, even as food banks experience record demand.

The common thread in all this is pettifogging regulations, rearing up in all their arcane, arbitrary and unbending glory. Common sense sometimes dictates that rules must be bent or broken in an emergency. But bureaucrats are not known for common sense.

It is a truism that bureaucrats are hidebound, unimaginitive creatures ill-suited to unexpected situations. And it’s easy to look at these bureaucratic snafus and want to punish somebody. You let thousands of people die because one checkbox wasn’t checked on the first application, and you sent them to the back of the line? What person will be held accountable for this?

We all know the answer to that. And sadly, that’s the way it has to be. Our complex civilization needs bureaucracies. Bureaucracies need rules and regulations. And the rules and regulations have to be uniformly followed, with bureaucrats punished for deviating. If you give bureaucrats discretion in following the rules, some of them will establish petty tyrannies and/or take bribes. Legal enforcement at the discretion of the enforcer creates a very tempting scope for self-interested wrongdoing.

So you need bureaucracies, you need bureaucrats, and you need the rules to be the rules. Except when you don’t. In an emergency, you want some bureaucrats to exercise some discretion. You want the institutions to become more adaptable, even at the cost of formal/correct procedure. The trick is to figure out how to incentivize good conduct in an “emergency” situation.

In normal times, a bureaucrat’s only incentive is to avoid liability to himself or the institution, which if everyone is honest means following the rules. Suppose a bureaucrat’s action or omission credibly leads to major harm or loss to the public. The bureaucrat can’t be held accountable so long as all the rules were followed to the letter. Truly rule-bound behavior and mindset is almost always a bureaucrat’s safest hold.

But suppose we adjusted the incentives in time of emergency? Suppose we stipulate:

- In time of emergency, bureaucratic agents are empowered to exercise discretion in some matters, relaxing procedures, making decisions above pay grade, or otherwise taking what in normal circumstances would be unacceptable risks.

- If an exercise of discretion leads to harm or loss, the agent will be indemnified provided he acted with reasonable information and intent, and with the expectation of a better outcome.

- If an exercise of discretion credibly saves a harm or loss, or brings a benefit, the agent should be suitably rewarded.

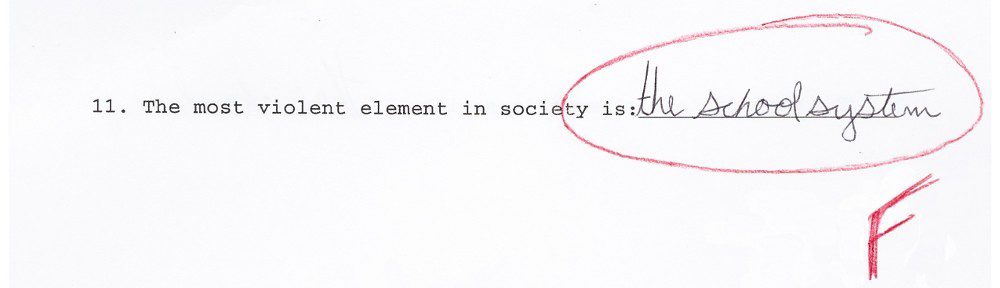

The issue of indemnification is paramount, and indemnification will be a recurring theme in this series. Perverse as it seems, in normal times liability management takes precedence over public service. The agent must feel confident that in times of emergency, public service comes first and it’s safe to put liability management in second place. For one in the bureacratic mindset, this is truly breaking the glass.